Historical Society of

Pottawattamie County

County Seat Council Bluffs, Iowa

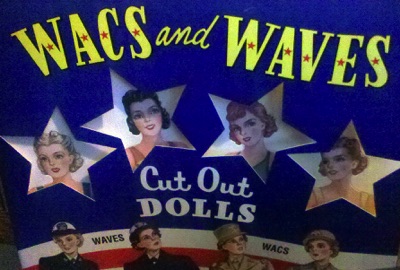

Women of the War

In 1942 the nation was at war, and "being in the military" for the most part meant "being male." But not completely.

A war requires a lot of personnel; excluding half the population because of their gender severely limited those available to serve. The WAAC (Woman's Army Auxiiary Corps) and WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service) were born to address this need.

Though the concept had been used in other countries and had been suggested by Army committees, the actual creation of the WAAC came from Congress without the blessing of the War Department. Representative Edith Rogers of Massachusetts introduced a bill to create the corps in 1941; it was approved in May, 1942, limited initially by executive order to 25,000 women. Within a few months the first 800 recruits were sent to Iowa to train at the Fort Des Moines Provisional Army Officer Training School.

Following the recommendation of Eleanor Roosevelt, Congress created the WAVES, a women's auxiliiary for the Navy. While the WACC were an auxilliary unit to serve *with* the Army, the WAVES were actually a part of the Navy, holding the same ranks and receiving the same pay as males. The WACC was merged into the Army as the WAC (Women's Army Corps) before the war was over.

Though referred to as "lady soldiers" and "lady sailors" the intent was not use in combat, but rather to release able bodied enlisted male personnel from clerical tasks. Also unlike the men, the recruits won't see the world; their assignments are restricted to the United States.

The first group of WAVES was trained at Smith College in Northhampton, Massachusetts. Council Bluffs had a native in that initial group. ALHS graduate Lt. Betty Evans was the second girl in the country to report for training. The 129 recruits ranged in age from 23 to 44 and were to be taught military etiquet, including how march.

The WAAC were initially assigned to one of three areas. The brightest were trained to be switchboard operators, those showing dexterity were to become mechanics, and those with least abilities assigned to be bakers. Many other duties were added as the War continued.

Newspaper stories suggest officers were a bit uneasy in how to deal with the women. Navy Captain Underwood was quoted as saying he hoped "this use of make-up business will solve itself." Every gentleman of the 1940s knew to stand when a lady entered a room, but if what if the gentleman outranked the lady? WAVES were forbidden to date enlisted seamen and "will be court martialed if they do anything sufficiently naughty to merit it." News reporters likewise showed departures from the norm, noting the class of WAVES at Smith College to be a mix of blonds, brunets, and red heads and that all were unmarried except one, not facts routinely reported in discussing military personnel.

While the WAAC, WAC, and WAVES provided valuable services to the war effort, their role was not universally supported. General Douglas MacArthur prized the women, saying they worked harder and complained less than the men, but not all his military colleagues agreed. Since the primary purpose of the women was to free up men for assignment to combat duty, some male soldiers who would prefer to remain in less dangerous jobs saw them as a threat. Female civlian employees sometimes saw the military women as competitprs for jobs that would have otherwise gone to them. Some of the nation wasn't ready for women in uniform. Occasionally recruits came home to find slander rather than respect, encountering rumors they were lesbian. Some conservatives and some religions saw inclusion of women in the armes forces as upsetting the social order.

That wasn't the case in Council Bluffs. Clippings from the Daily Nonpareil and Omaha World Herald in the Historical Society archives show both newspapers followed the progress of local WAVES recruit Betty Evans closely, giving much attention to her promotions and progress.

Lt. Evans graduated from Abraham Lincoln High School in 1927 and Drake University in 1931 where she studied journalism. When the war broke out she left an advertising agency job to become the director of publicity of the woman's division of the war bond and stamp sales. When the WAVES opportunity came along she decided to enlist herself. When asked about this she told a reporter women in her family women weren't scared of war. She explained when her great-grandfather was in the civil war her great-grandmother borrowed a friend's buggy and traveled to the battle zone to await the outcome. When her great-grandfather exclaimed, "Good God,Sadie, what areyou doing here?" She replied, "If it's not too tough for you here I guess it isn't for me either!"

Lt. Evans was promoted to the bureau of aeronautics, motion picture division, in 1943 where she was given the task of writing scripts for training films. Following the war she became government affairs editor for the United States Chamber of Commerce in Washington.

Council Bluffs was at the very forefront of opening doors for women in the military. The nurses of Mobile Hospital #1, mustered for duty First World War duty in Council Bluffs and composed of local nurses, were virtually the first American women allowed at at the front lines of a battle.

Council Bluffs women were military trendsetters. Local nurses were the first females ever permitted in a war zone as a part of Mobile Hospital #1 in World War I. A Council Bluffs woman was the second in the nation to enlist in the WAVES, and the first WAC unit trained in Iowa.